Paul Maher - Window on a city

private spaces – shared landscape

29 April - 21 May 2023

OPENING/MEET THE ARTIST Saturday 29 April, 11am – 5pm ALL WELCOME

- Download Window on a City catalogue (PDF 3.4mb)

- Listen to Paul Maher on ABC Newcastle Breakfast (mp3 2.8mb)

“I’ve been drawing in Newcastle’s European heart from buildings built in the early 1900s. Owners have let me come in and draw from private spaces, the views that have remained constant of the sea and harbour.

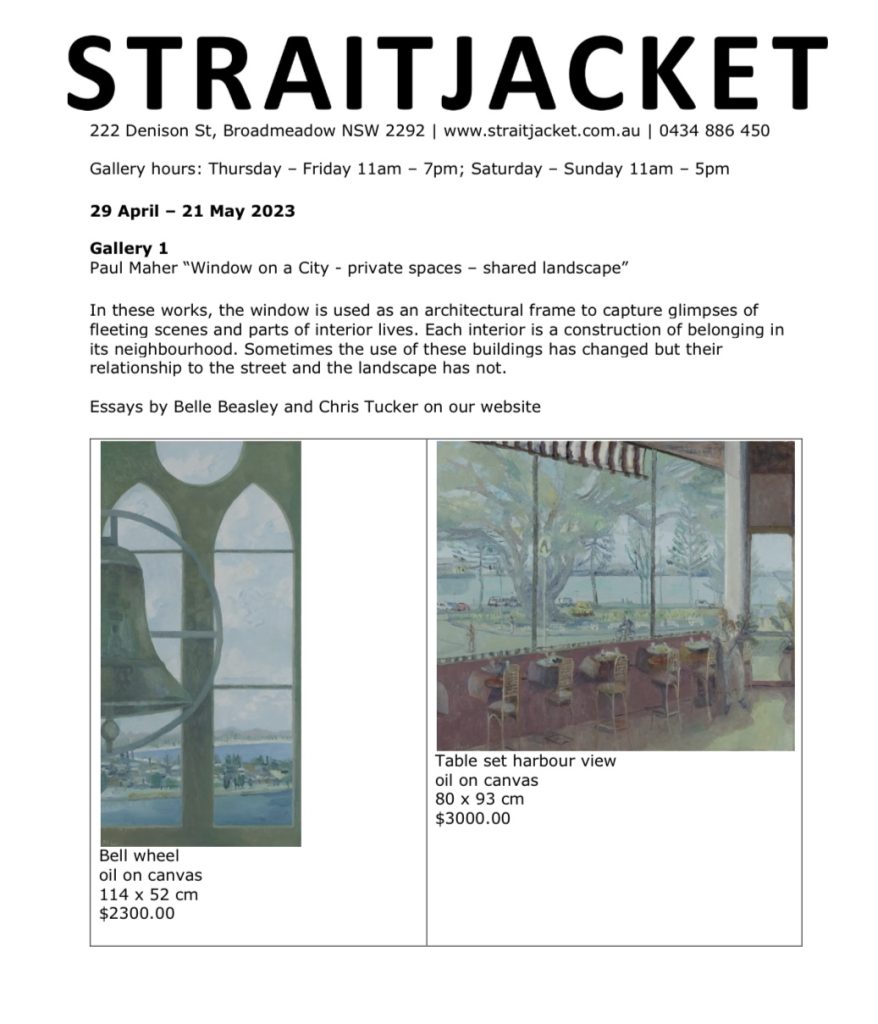

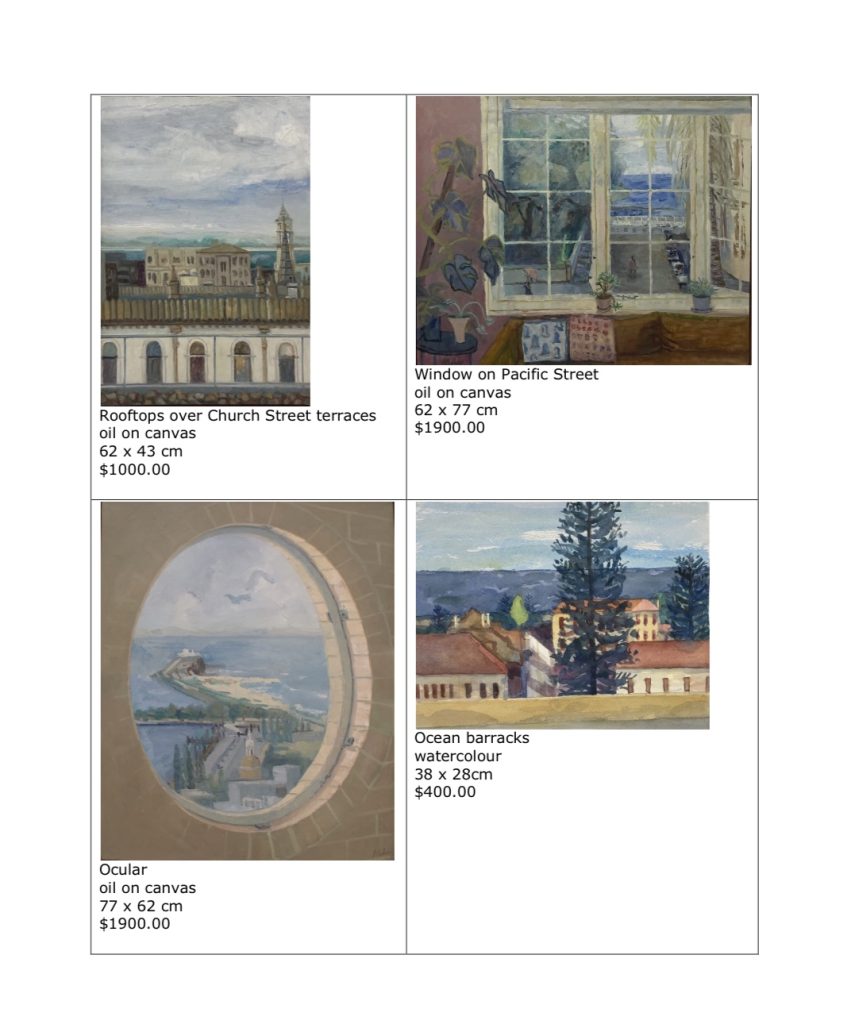

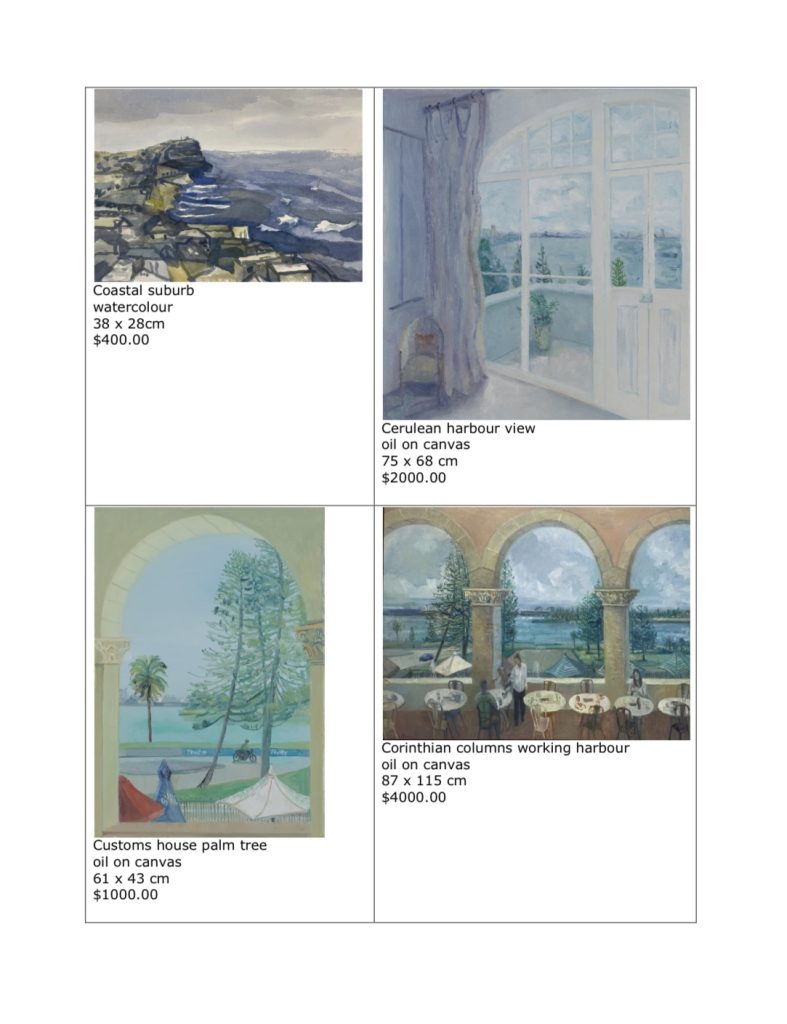

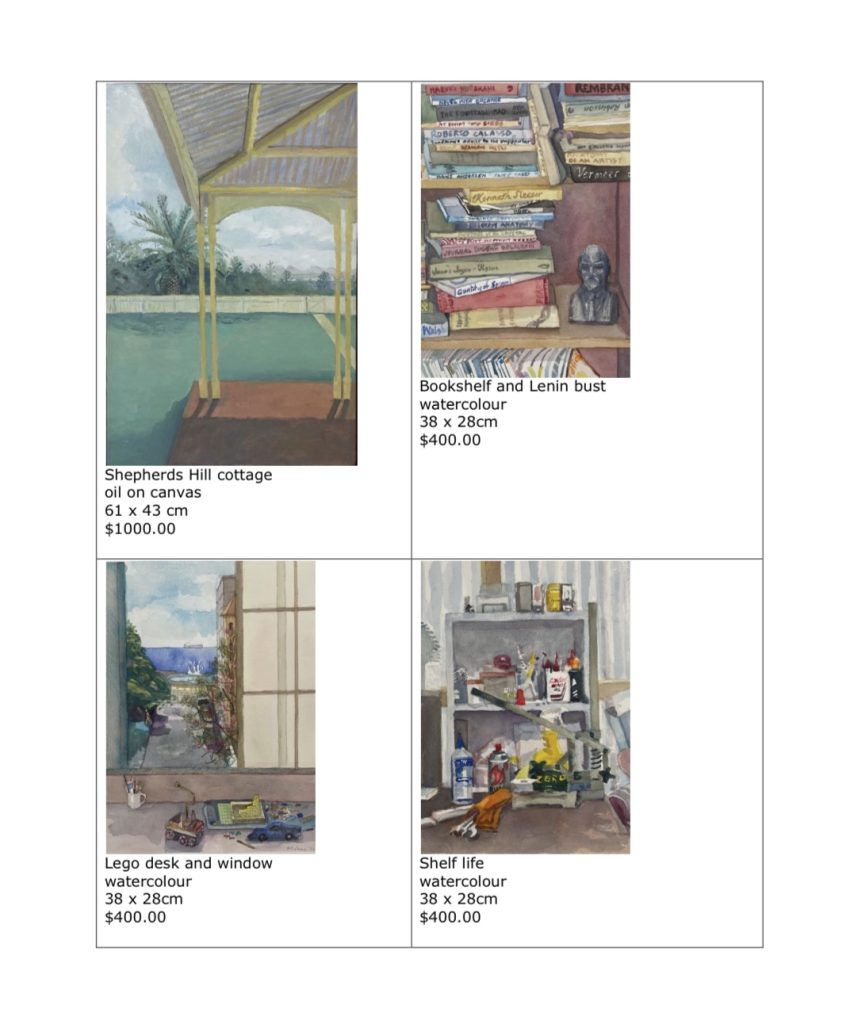

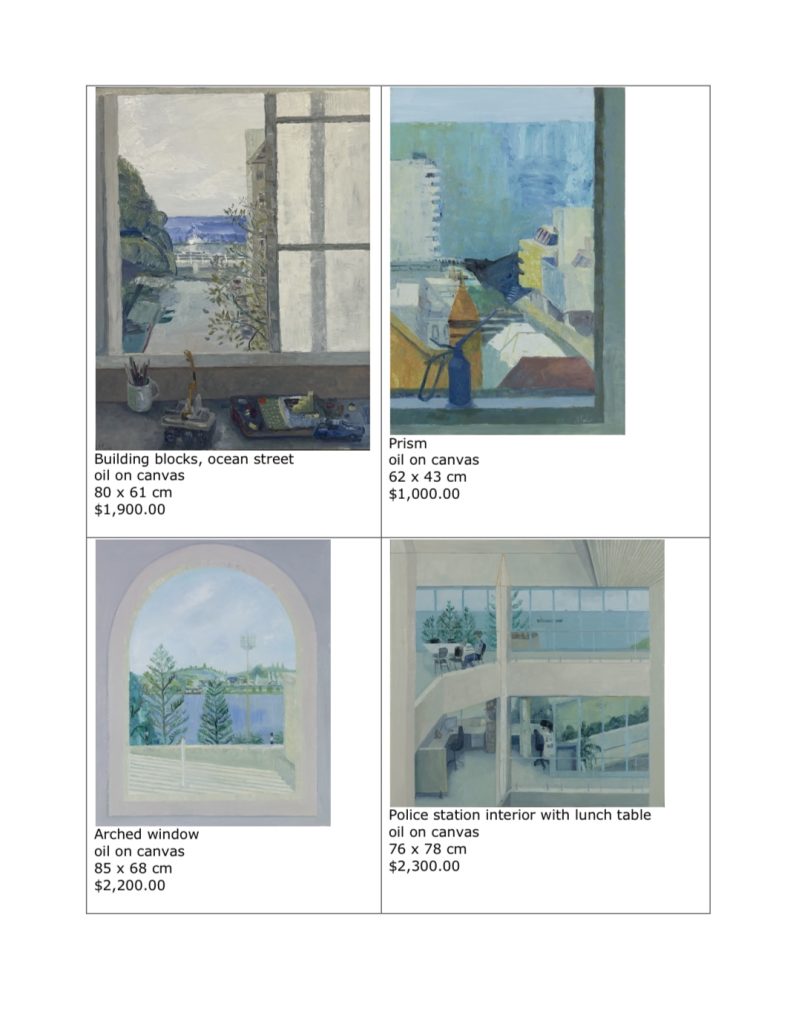

In these works, the window is used as an architectural frame to capture glimpses of fleeting scenes and parts of interior lives. Each interior is a construction of belonging in its neighbourhood. Sometimes the use of these buildings has changed but their relationship to the street and the landscape has not.

I’m preoccupied with making this connection visible through the most elemental means; structure, space and light are fused. The drawings are abbreviations of what I see but are enough to evoke the experience of being there back in the studio. ” Paul Maher

Words by Chris Tucker

“There’s something quite intimate about a distant gaze that also brings into focus the things that are close, that we can reach out to, touch, and move about. Paul Maher’s exhibition Window on a City dwells on this idea – where the near and far are at opposite ends of how we view the world, but yet tied together as dependents who aren’t entirely sure what to make of the other. There’s also a curious conversation between the landscape, that we observe at some distance to ourselves and have almost no control over, and those things so up-close and personal to us that we almost look right through them, not seeing them at all. A cup filled with pencils sits on a desk while the ocean crashes against a beach, like it has for thousands of years. As the eye shifts between the two, I’m not sure which has the better hand, is it here or there?

Window on a City invites us to imagine both the near and far at once, something that should be a common enough experience as we move about, but here on the walls, together in the same frame, and in equal enough ways, their tension becomes obvious. In reality, the near and the far aren’t that different from each other – a far away place might at another time be quite near. It’s not necessarily that they’re made of different things, time just locates them as different places for us. It’s the frame of the window that curates the distance for us. It keeps the near and far apart, defines their boundaries, and sets up a place where they can begin to tell their stories. The tension in framing these different worlds through the window is kept by the secrets each holds from the other – they have different stories to tell, and in conversation they only share what each can understand. The near is more comfortable with stories about my person, and those that make sense of my body; decorated cushions sit on a worn lounge, plants from the outside dutifully cared for in pots, artefacts with no meaning excepting their owners, and utensils scaled to fit a hand that’s no longer in picture…they all remind us of how we make the world around us. In contrast, the far appears to scream a present made by others, while whispering the past, and those places that might yet come – what secrets do you hold?

Windows let the outside in. They bring light and air, but by posing the inside and outside together in the same scene, they also weave our different lives together from the comfort of a place we know well. Window on a City celebrates these worlds, reminding us that looking on to a window is an entirely different way of being in the world compared with looking into one.”

Notes on Looking / Ways of Seeing

written for Paul Maher by Belle Beasley

In the newly opened North Wing of the Art Gallery of NSW lies a quote: “If you paint everything but the figure, the figure will emerge.” The quote pertains to a painting by the American artist Reggie Burrows Hodges, depicting two faceless figures surrounded by objects of their domestic life. The quote’s suggestion, that the faces of the two ambiguous characters in his moody portrait are realised by virtue of their context, is relevant too in the survey of landscapes that Paul Maher has brought together for Window on a City.

Emphasising the constancy of the natural world against the fluctuating interiors of historical Hunter buildings, Window on a City explores the contrasting moods of interior and exterior, and grapples with tension between the natural and the man-made. However, also brought to the fore throughout the exhibition is a speculation of character. Whilst we feast our eyes upon sumptuous seascapes, richly adorned windows and busy domestic spaces, our gaze is simultaneously directed away from scenery and towards the person just out of view. We are prompted to delve into our imaginations and consider the histories, complexities, and mundanities of the lives lived behind the frame – the figures obscured from the canvas.

This was an unintentional layer of meaning for Paul. Throughout the process of cataloguing the view from different vantage points, the still-life scenes that bled into the frame revealed a richness. The shape of the window, its ornamentations, its proximity to a seat, the style of furnishing, the genre of books strewn across the desk amidst all number of miscellaneous items – the figure inside, watching from the window, came alive through the recreation of the view.

He likens the layers of stories contained just out of reach by the limits of the canvas to an experience on the top floor of the old David Jones Building, now the QT, where he witnessed several layers of wallpaper being peeled back, a nod to the many revamps the space had gone through since it’s construction. Initially interested in capturing the landscape through the framing of the window, Window on a City has resulted in the observation of not just landscapes, but of lives.

The landscape, one of the oldest art historical genres, has been proven time and time again as a rich subject, compositional challenge, and mode of escapism for artists and audiences alike. Incorporating a window to frame the scenery tempers this daydream by encasing nature’s daunting wilderness with a sense of safety. Positioned behind the glass, a viewer can be projected out into the sublime, bucolic pastures, while simultaneously remaining in their protective dwelling. Surrounded by creature comforts and going about their daily lives.

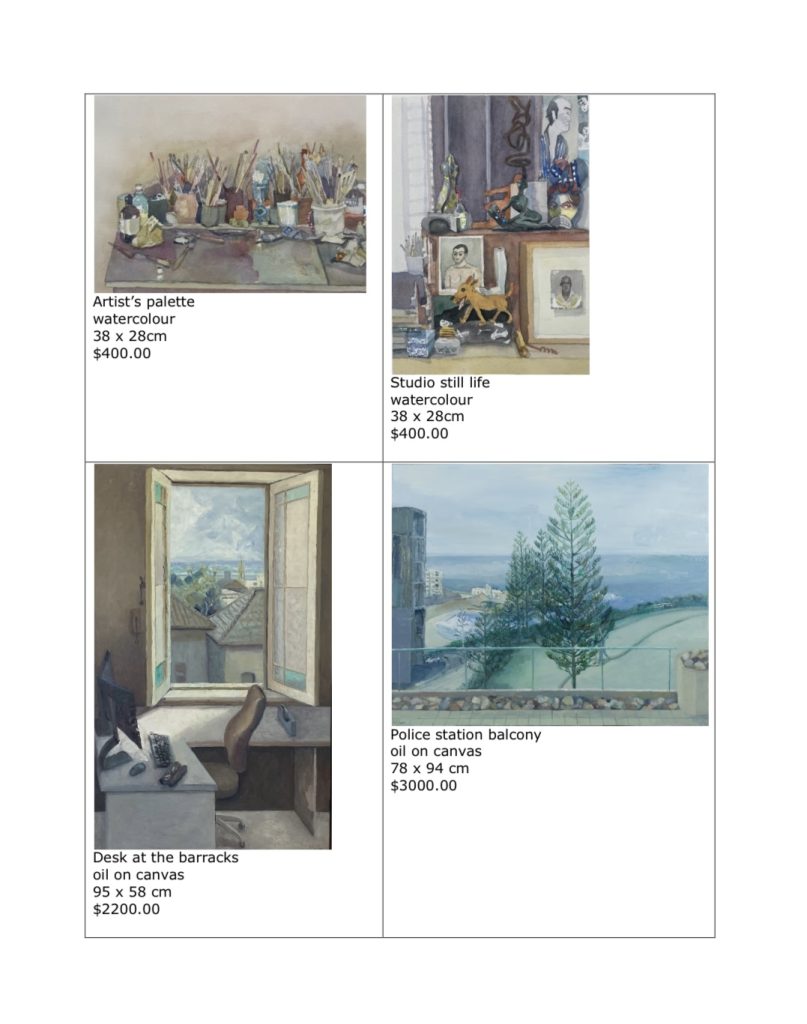

In selecting windows attached to historically significant buildings, Paul extrapolates on the varied existences from within these spaces, both real, and imagined. The ground floor of the old David Jones, where you shopped for your first respectable button-up for that big interview. The brutalist façade of the Newcastle Police Station, recalling a shameful run-in with the cops in your early twenties you’d rather not be reminded of. And the panoramic view of the Christchurch Cathedral Bell Tower, conjuring up visions of Newcastle’s own Quasimodo-like character, dutifully climbing the stairwell every day. Each of the works in Maher’s exhibition tells a story – one of the land, one of the building, and one of the life lived within the four walls. A meditation on the interwoven nature of these stories, Paul Maher’s Window on the City reminds us that we glean as much from looking in, as we do from looking out.